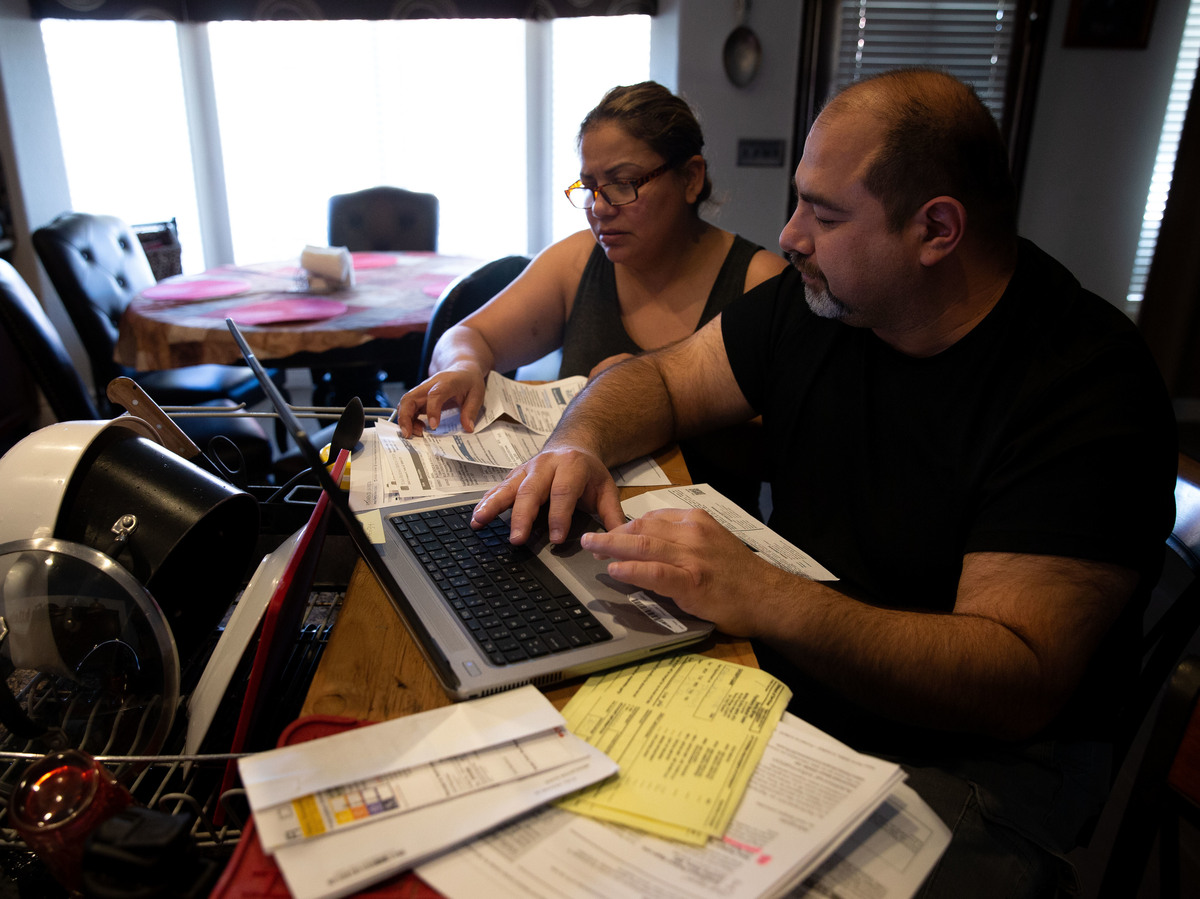

Claudia and Jesús Fierro of Yuma, Ariz., review their medical bills. They pay $1,000 a month for health insurance yet still owed more than $7,000 after two episodes of care at the local hospital.

Lisa Hornak for Kaiser Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Lisa Hornak for Kaiser Health News

Claudia and Jesús Fierro of Yuma, Ariz., review their medical bills. They pay $1,000 a month for health insurance yet still owed more than $7,000 after two episodes of care at the local hospital.

Lisa Hornak for Kaiser Health News

The Fierro family of Yuma, Ariz., had a string of bad medical luck that started in December 2020.

That’s when Jesús Fierro Sr. was admitted to the hospital with a serious case of COVID-19. He spent 18 days at Yuma Regional Medical Center, where he lost 60 pounds. He came home weak and dependent on an oxygen tank.

Then, in June 2021, his wife, Claudia Fierro, fainted while waiting for a table at the local Olive Garden restaurant. She felt dizzy one minute and was in an ambulance on her way to the same medical center the next. She was told her magnesium levels were low and was sent home within 24 hours.

The family has health insurance through Jesús Sr.’s job, but it didn’t protect the Fierros from owing thousands of dollars. So when their son Jesús Fierro Jr. dislocated his shoulder, the Fierros — who hadn’t yet paid the bills for their own care — opted out of U.S. health care and headed south to the U.S.-Mexico border.

And no other bills came for at least one member of the family.

The patients: Jesús Fierro Sr., 48; Claudia Fierro, 51; and Jesús Fierro Jr., 17. The family has Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas health insurance through Jesús Sr.’s employment with NOV, formerly National Oilwell Varco, an American multinational oil company based in Houston.

Medical services: For Jesús Sr., 18 days of inpatient care for a severe case of COVID-19. For Claudia, fewer than 24 hours of emergency care after fainting. For Jesús Jr., a walk-in appointment for a dislocated shoulder.

Total bills: Jesús Sr. was charged $3,894.86. The total bill was $107,905.80 for COVID-19 treatment. Claudia was charged $3,252.74, including $202.36 for treatment from an out-of-network physician. The total bill was $13,429.50 for less than one day of treatment. Jesús Jr. was charged $5 (70 pesos) for an outpatient visit that the family paid in cash.

Service providers: Yuma Regional Medical Center, a 406-bed nonprofit hospital in Yuma, Ariz. It’s in the Fierros’ insurance network. And a private doctor’s office in Mexicali, Mexico, which is not.

What gives: The Fierros were trapped in a situation in which more and more Americans find themselves. They are what some experts term “functionally uninsured.” They have insurance — in this case, through Jesús Sr.’s job, which pays $72,000 a year. But their health plan is expensive, and they don’t have the liquid savings to pay their share of the bill. The Fierros’ plan says their out-of-pocket maximum is $8,500 a year for the family. And in a country where even a short stay in an emergency room is billed at a staggering sum, that means minor encounters with the medical system can take virtually all the family’s disposable savings, year after year. And that’s why the Fierros opted out of U.S. health care for their son.

According to the terms of the insurance plan, which has a $2,000 family deductible and 20{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} coinsurance, Jesús Sr. owed $3,894.86 out of a total bill of nearly $110,000 for his COVID-19 care in late 2020.

The Fierros are paying off that bill — $140 a month — and still owe more than $2,500. In 2020, most insurers agreed to waive cost-sharing payments for COVID-19 treatment after the passage of federal coronavirus relief packages that provided emergency funding to hospitals. But waiving treatment costs was optional under the law. And although Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas has a posted policy saying it would waive cost-sharing through the end of 2020, the insurer didn’t do that for Jesús Sr.’s bill. Carrie Kraft, a spokesperson for the insurer, wouldn’t discuss why his bill was not waived.

(More than two years into the coronavirus pandemic and with vaccines now widely available to reduce the risk of hospitalization and death, most insurers again charge patients their cost-sharing portion.)

On Jan. 1, 2021, the Fierros’ deductible and out-of-pocket maximum reset. So when Claudia fainted — a fairly common occurrence and rarely indicative of a serious problem — she was sent by ambulance to the emergency room, leaving the Fierros with another bill of more than $3,000. That kind of bill is a huge stress on many American families; fewer than half of U.S. adults have enough savings to cover a surprise $1,000 expense. In recent polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation, “unexpected medical bills” ranked second among family budget worries, behind gas prices and other transportation costs.

The new bill for the fainting spell destabilized the Fierros’ household budget. “We thought about taking a second loan on our house,” said Jesús Sr., a Los Angeles native. When he called the hospital to ask for financial assistance, he said, people he spoke with strongly discouraged him from applying. “They told me that I could apply but that it would only lower Claudia’s bill by $100,” he said.

So when Jesús Jr. dislocated his shoulder when boxing with his brother, the family headed south.

Jesús Sr. asked his son, “Can you bear the pain for an hour?” The teen replied, “Yes.”

Father and son took the hourlong trip to Mexicali, Mexico, to Dr. Alfredo Acosta’s office.

The Fierros don’t consider themselves “health tourists.” Jesús Sr. crosses the border into Mexicali every day for his work, and Mexicali is Claudia’s hometown. They’ve been traveling to the neighborhood known as La Chinesca (Chinatown) for years to see Acosta, a general practitioner, who treats the asthma of their youngest son, Fernando, 15. Treatment for Jesús Jr.’s dislocated shoulder was the first time they had sought emergency care from the physician. The price was right, and the treatment effective.

A visit to a U.S. emergency room likely would have involved a facility fee, expensive X-rays and perhaps a specialist’s evaluation — which would have generated thousands of dollars in bills. Acosta adjusted Jesús Jr.’s shoulder so that the bones aligned in the socket and prescribed him ibuprofen for soreness. The family paid cash on the spot.

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention doesn’t endorse traveling to another country for medical care, the Fierros are among millions of Americans each year who do. Many of them are fleeing expensive care in the U.S., even with health insurance.

Acosta, who is from the Mexican state of Sinaloa and is a graduate of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, moved to Mexicali 20 years ago. He witnessed firsthand the growth of the medical tourism industry.

He sees about 14 patients a day (no appointment necessary), and 30{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 40{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of them are from the United States. He charges $8 for typical visits.

In Mexicali, a mile from La Chinesca, where the family doctors have their modest offices, there are medical facilities that rival those in the United States. The facilities have international certification and are considered expensive, but they are still cheaper than hospitals in the United States.

Resolution: Both Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas and Yuma Regional Medical Center declined to discuss the Fierros’ bills with KHN, even though Jesús Sr. and Claudia gave written permission for them to do so.

In a statement, Yuma Regional Medical Center spokesperson Machele Headington said, “Applying for financial support starts with an application — a service we extended, and still extend, to these patients.”

In an email, Kraft, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas spokesperson, said: “We understand the frustration our members experience when they receive a bill containing COVID-19 charges that they do not understand, or feel may be inappropriate.”

The Fierros are planning to apply to the hospital for financial support for their outstanding debts. But Claudia said never again: “I told Jesús, ‘If I faint again, please drive me home,’ ” rather than call an ambulance.

“We pay $1,000 premium monthly for our employment-based insurance,” added Jesús. “We should not have to live with this stress.”

The takeaway: Be aware that your deductible “meter” starts over every year and that virtually any emergency care can generate a bill in the thousands of dollars and may leave you owing your deductible and most of your out-of-pocket maximum.

Also be aware that even if you seem not to qualify for financial assistance based on a hospital’s policy, you can apply and explain your circumstances. Because of the high cost of care in the U.S., even many middle-income people qualify. And many hospitals give their finance departments leeway to adjust bills. Some patients discover that if they offer to pay cash on the spot, the bill can be reduced dramatically.

All nonprofit hospitals have a legal obligation to help patients: They pay no tax in exchange for providing “community benefit.” Make a case for yourself, and ask for a supervisor if you get an initial no.

For elective procedures, patients can follow the Fierros’ example, becoming savvy health care shoppers. Recently, Claudia needed an endoscopy to evaluate an ulcer. The family called different facilities and discovered a $500 difference in the cost of an endoscopy. They will soon drive to a medical center in Central Valley, California, two hours from home, for the procedure.

The Fierros didn’t even consider going back to their local hospital. “I don’t want to say, ‘Hello’ and receive a $3,000 bill,” joked Jesús Sr.

Stephanie O’Neill contributed the audio portrait with this story.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by KHN and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

More Stories

The Introvert’s Sanctuary: Why Creating a Home Gym Could Transform Your Wellbeing

Health and Fitness: A Holistic Approach

10 killer 10-minute workouts to transform your fitness routine