Summary

Health coverage performs a important job in enabling people today to entry overall health care and shielding households from large clinical charges. Persons of colour have faced longstanding disparities in overall health protection that add to disparities in wellbeing. This transient examines developments in health protection by race/ethnicity from 2010 by means of 2021 and discusses the implications for health and fitness disparities. All noted discrepancies in between groups and several years described in the text are statistically substantial at the p<0.05 level. It is based on KFF analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) data for the nonelderly population.

Following several years of rising uninsured rates during the Trump Administration, there were small gains in coverage across most racial/ethnic groups between 2019 and 2021. The coverage gains between 2019 and 2021 were largely driven by increases in Medicaid coverage, reflecting policies to stabilize and expand access to affordable coverage that were implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, including a requirement that states keep Medicaid enrollees continuously enrolled during the public health emergency (PHE). These coverage gains helped narrow percentage point differences in uninsured rates between people of color and White people.

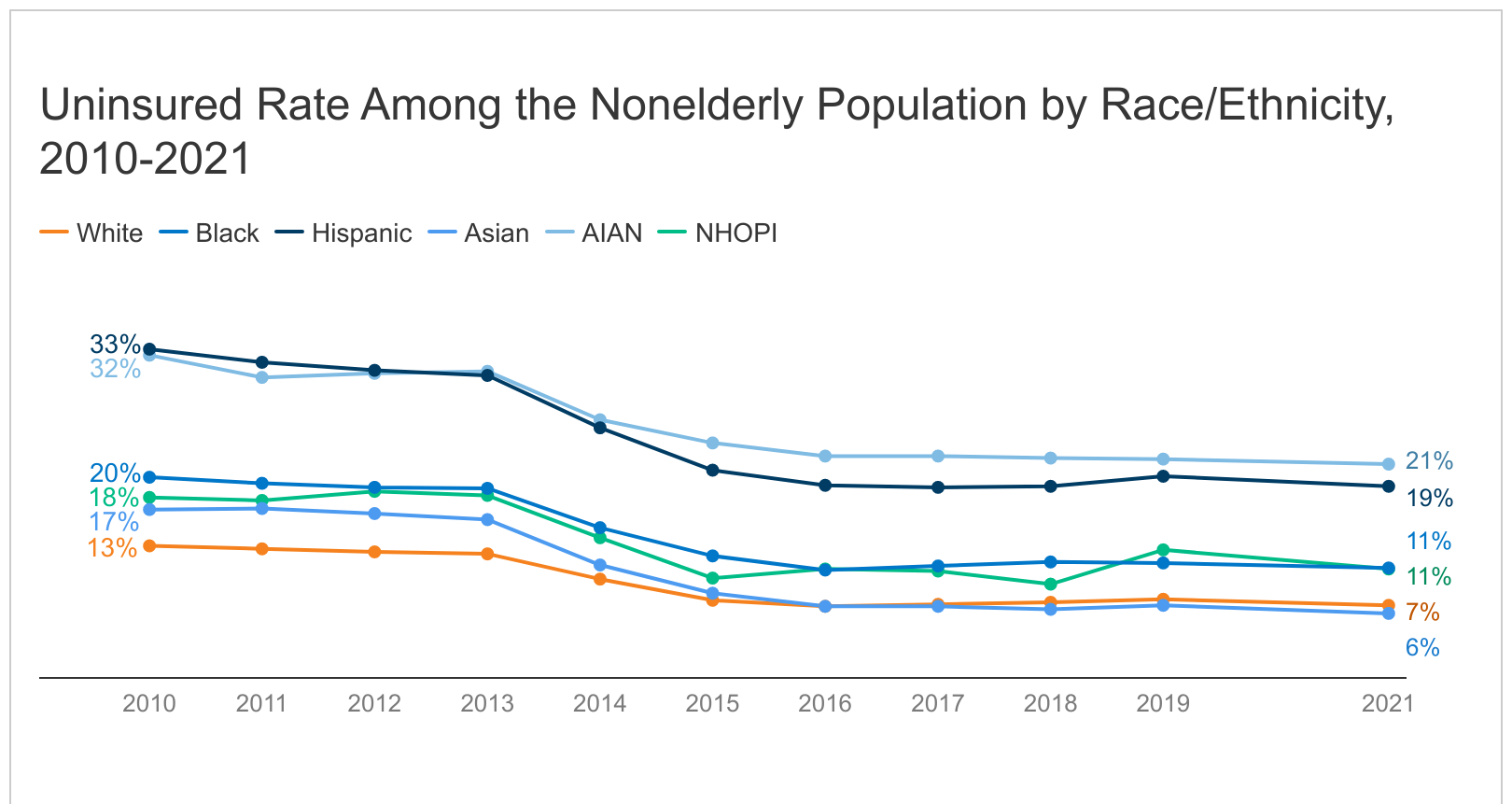

Despite these coverage gains, disparities in coverage persisted as of 2021. Nonelderly American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and Hispanic people had the highest uninsured rates at 21.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} and 19.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}, respectively as of 2021. Uninsured rates for nonelderly Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) and Black people (10.8{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} and 10.9{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}, respectively) also were higher than the rate for their White counterparts (7.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}). Coverage disparities have persisted over time despite these recent gains and large earlier gains in coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). For example, between 2010 and 2021, the uninsured rate for AIAN people grew from 2.5 to 2.9 times higher than the uninsured rate for White people, the Hispanic uninsured rate remained over 2.5 times higher than the rate for White people, and Black people remained 1.5 times more likely to be uninsured than White people.

Uninsured rates in states that have not expanded Medicaid are nearly twice as high as rates in expansion states for nonelderly White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian people as of 2021. Most racial/ethnic groups are more likely to be uninsured in non-expansion states compared to expansion states, and the gaps in coverage rates between Black and Hispanic people and White people are larger in non-expansion states compared with expansion states. However, the relative risk of being uninsured for people of color compared to White people is similar in expansion and non-expansion states.

The ongoing gaps in coverage for people of color and the direction that coverage moves in going forward has implications for people’s access to care and overall health and well-being and broader disparities in health and health care. Looking ahead, the end of the PHE may contribute to disproportionate coverage declines among people of color, which could further widen the coverage gaps they already face, and, in turn, exacerbate broader disparities in health and health care. As such, efforts to prevent coverage losses and further close coverage disparities are an important component of efforts to address longstanding racial disparities in health. However, to advance health equity, it also will be important to address other inequities within the health care system as well as inequities across the broad range of social and economic factors that drive health.

Trends in Uninsured Rates by Race/Ethnicity, 2010-2021

Prior to the enactment of the ACA in 2010, people of color were at much higher risk of being uninsured compared to White people, with Hispanic and AIAN people at the highest risk of lacking coverage (Figure 1). The higher uninsured rates among people of color reflected more limited access to affordable health coverage options. Although the majority of individuals have at least one full-time worker in the family across racial and ethnic groups, people of color are more likely to live in low-income families that do not have coverage offered by an employer or to have difficulty affording private coverage when it is available. While Medicaid helped fill some of this gap in private coverage, prior to the ACA, Medicaid eligibility for parents was limited to those with very low incomes (often below 50{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of the poverty level), and adults without dependent children—regardless of how poor—were ineligible under federal rules.

Between 2010 and 2016, there were large gains in coverage across racial/ethnic groups under the ACA, but people of color remained more likely to be uninsured. The ACA created new coverage options for low- and moderate-income individuals. These included provisions to extend dependent coverage in the private market up to age 26 and prevent insurers from denying people coverage or charging them more due to health status that went into place. Further, beginning in 2014, the ACA expanded Medicaid coverage to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of poverty in states that adopted the expansion and made tax credits available to people with incomes up to 400{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of poverty to purchase coverage through a health insurance Marketplace. Following the ACA’s enactment in 2010 through 2016, coverage increased across all racial/ethnic groups, with the largest increases occurring after implementation of the Medicaid and Marketplace coverage expansions in 2014. Nonelderly Hispanic people had the largest percentage point increase in coverage, with their uninsured rate falling from 32.6{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 19.1{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}. Nonelderly Black, Asian, and AIAN people also had larger percentage point increases in coverage compared to White people over that period. Despite these larger gains, nonelderly AIAN, Hispanic, Black, and NHOPI people remained more likely than their White counterparts to be uninsured as of 2016.

Beginning in 2017, coverage gains began reversing, and the number of uninsured increased for three consecutive years. The uninsured rate for the total nonelderly population increased from 10.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} in 2016 to 10.9{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} in 2019. Nonelderly Hispanic people had the largest statistically significant increase in their uninsured rate over this period (from 19.1{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 20.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}). There were also small but statistically significant increases in the uninsured rates among nonelderly White and Black people, which rose from 7.1{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 7.8{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} and 10.7{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 11.4{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}, respectively, between 2016 and 2019. Rates for nonelderly AIAN, NHOPI, and Asian people did not have a significant change. These coverage losses likely reflected policy changes made by the Trump Administration after taking office in 2017 that reduced access to and enrollment in coverage. These changes included decreased funds for outreach and enrollment assistance, guidance encouraging states to seek waivers to add new eligibility requirements for Medicaid coverage, and changes to public charge immigration policy that made some immigrant families more reluctant to participate in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

After increasing for several years prior to the pandemic, uninsured rates declined between 2019 and 2021. Nearly 1.5 million nonelderly people gained coverage between 2019 and 2021 as the uninsured rate dropped from 10.9{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 10.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}. (Because of disruptions in data collection during the first year of the pandemic, the Census Bureau did not release 1-year ACS estimates in 2020.) Hispanic people had the largest percentage point increase in coverage, with their uninsured rate falling from 20.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} in 2019 to 19.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} in 2021. There were also smaller but statistically significant declines in uninsured rates among Asian people (from 7.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 6.4{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}), Black people (from 11.4{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 10.9{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}), and White people (from 7.8{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} to 7.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}) during this period. These coverage gains were primarily driven by increases in Medicaid coverage, which offset declines in employer-sponsored coverage over the period. AIAN and NHOPI people did not have statistically significant changes in coverage over this period.

The coverage gains between 2019 and 2021 largely reflect policies adopted during the pandemic to stabilize coverage in Medicaid and enhance subsidies to purchase Marketplace coverage. Specifically, provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), enacted at the start of the pandemic, prohibit states from disenrolling people from Medicaid until the month after the COVID-19 PHE ends in exchange for enhanced federal funding. Coverage gains also likely reflected enhanced ACA Marketplace subsidies made available by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and renewed for another three years in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA), boosted outreach and enrollment efforts, a Special Enrollment Period for the Marketplaces provided in response to the pandemic, and low Marketplace attrition, Additionally, in 2019, the Biden Administration reversed changes the Trump Administration previously made to public charge immigration policies that had increased reluctance among some immigrant families to enroll in public programs, including health coverage.

Coverage by Race and Ethnicity as of 2021

As of 2021, nonelderly AIAN, Hispanic, NHOPI, and Black people continued to face coverage disparities (Figure 2). Nonelderly AIAN and Hispanic people had the highest uninsured rates at 21.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} and 19.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}, respectively as of 2021. Uninsured rates for nonelderly NHOPI and Black people (10.8 and 10.9{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}, respectively) also were higher than the rate for their White counterparts (7.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}). Coverage disparities have persisted over time even with recent gains and the large earlier gains in coverage under the ACA. For example, between 2010 and 2021, the uninsured rate for AIAN people grew from 2.5 to 2.9 times higher than the uninsured rate for White people, the Hispanic uninsured rate remained over 2.5 times higher than the rate for White people, and Black people remained 1.5 times more likely to be uninsured than White people.

Medicaid and CHIP coverage help fill gaps in private coverage and reduce coverage disparities for children, but some disparities in children’s coverage remain (Figure 2). Medicaid and CHIP cover larger shares of children than adults, reflecting more expansive eligibility levels for children. This coverage helps fill gaps in private coverage, particularly for children of color, with over half of Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI children covered by Medicaid and CHIP. However, there remain some disparities in children’s coverage. For example, AIAN children are over three times as likely as their White counterparts to lack coverage, with 13.2{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of AIAN children uninsured compared with 4.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of White children. Moreover, Hispanic children are over twice as likely as White children to be uninsured (8.6{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} vs. 4.0{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161}).

Among the total nonelderly population, uninsured rates in states that have not expanded Medicaid are nearly twice as high as rates in expansion states for nonelderly White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian people as of 2021 (Figure 3). Most racial/ethnic groups are more likely to be uninsured in non-expansions states compared to expansion states. Further, the gaps in coverage rates between Black and Hispanic people and White people are larger in non-expansion states. However, the relative risk of being uninsured for people of color compared with White people is similar in expansion and non-expansion states. For example, nonelderly Hispanic people are roughly 2.5 times as likely as nonelderly White people to lack coverage in both expansion and non-expansion states. These differences in coverage by expansion status are primarily driven by differences in coverage rates among nonelderly adults. However, Hispanic, Black, Asian, and White children in non-expansion states also are more likely to be uninsured than those in expansion states. For example, 13.7{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of Hispanic children in non-expansion states are uninsured, compared to 5.9{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of Hispanic children in expansion states.

There are opportunities to increase coverage by enrolling eligible people in Medicaid or Marketplace coverage, but eligibility varies across racial and ethnic groups, and many remain ineligible for assistance. Prior to the pandemic, over half of the nonelderly uninsured were eligible for financial assistance through Medicaid or the ACA Marketplaces. The ARPA, enacted in 2021, further increased access to subsidized health coverage through temporary increases and expansions in eligibility for subsidies to buy health insurance through the health insurance Marketplaces, which were extended under the IRA. While many nonelderly uninsured are eligible for health coverage assistance, some remain ineligible because their state did not expand Medicaid, they do not have access to an affordable Marketplace plan or offer of employer coverage, or due to their immigration status. Eligibility for coverage varies across racial and ethnic groups, reflecting differences in the share of people living in states that have not expanded Medicaid and sociodemographic differences. For example, uninsured nonelderly Black people are more likely than their White counterparts to fall in the Medicaid “coverage gap” because a greater share live in states that have not implemented the Medicaid expansion (Figure 4). As of November 2022, 11 states have not adopted the ACA provision to expand Medicaid to adults with incomes through 138{6f90f2fe98827f97fd05e0011472e53c8890931f9d0d5714295052b72b9b5161} of poverty. In these states, adults with incomes under poverty fall in the “coverage gap” because they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for ACA Marketplace premium subsidies.

Uninsured nonelderly Hispanic, NHOPI, and Asian people are less likely than their White counterparts to be eligible for coverage because they include larger shares of noncitizens who are subject to eligibility restrictions for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage (Figure 5). Lawfully present immigrants face eligibility restrictions for Medicaid coverage, with many having to wait five years after obtaining lawful status before they may enroll in Medicaid. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid and are prohibited from purchasing coverage through the Marketplaces.

Looking Ahead

Policies implemented amid the COVID-19 pandemic have helped to stabilize coverage and contributed to gains in coverage. The coverage gains experienced amid the COVID-19 pandemic were largely driven by an increase in Medicaid coverage, which offset declines in employer-sponsored coverage. As noted, temporary continuous enrollment provisions have stabilized Medicaid coverage during the PHE, contributing to rises in enrollment. Additionally, the temporary increases and expansions in eligibility for subsidies to buy health insurance through the health insurance Marketplaces provided under ARPA, which were extended through 2025 under the IRA, have likely contributed to coverage gains. Enrollment in the Marketplaces has also reached a record high, following the availability of enhanced the subsidies, boosted outreach efforts, and an extended enrollment period. Analysis suggests that Marketplace enrollment increases between 2020 and 2022 were particularly large for Hispanic, Black and AIAN people. Even with these recent actions, gaps in coverage remain. Some uninsured individuals remain ineligible for assistance through Medicaid or the Marketplace subsidies, including immigrants who face eligibility restrictions for coverage.

Opportunities remain to increase coverage and narrow disparities by enrolling eligible people in Medicaid or Marketplace coverage, and these opportunities would increase if additional states adopted Medicaid expansion. Given that most uninsured people are eligible for Medicaid or Marketplace coverage, outreach and enrollment efforts could further increase coverage and potentially narrow coverage disparities. To assist with outreach and enrollment efforts, the Biden Administration increased funding for Navigators for the 2022 Open Enrollment Period, contributing to record levels of Marketplace enrollment in 2022, and has made an additional investment of $98.9 million in Navigator funding for the 2023 Open Enrollment Period. In addition, implementation of the Medicaid expansion in the remaining 11 states that have not yet expanded would further increase eligibility for coverage among the remaining uninsured for all groups, but disproportionately for Black people. ARPA included fiscal incentives for states that have not yet adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion to do so. However, it remains unclear, which if any remaining states will implement the Medicaid expansion. Data show that, if all remaining states expanded Medicaid, six in ten uninsured adults who would become eligible would be people of color. Research further shows that Medicaid expansion is associated with reductions in racial/ethnic disparities in health coverage as well as narrowed disparities in health outcomes for Black and Hispanic individuals, particularly for measures of maternal and infant health.

The end of the PHE may lead to coverage losses and widening disparities. The Medicaid continuous enrollment requirement is tied to the PHE, which is in effect through mid-January 2023, although it is expected the PHE will be extended again because the Biden administration has said it will give states a 60-day notice before ending the PHE and that notice was not issued in November 2022. Once the PHE ends, states will resume Medicaid redeterminations and will disenroll people who are no longer eligible or who are unable to complete the renewal process even if they remain eligible. KFF estimates that between 5 and 14 million people could lose Medicaid coverage, including many who newly gained coverage in the past year. Other research shows that Hispanic and Black people are likely to be disproportionately impacted by the expiration of the continuous enrollment requirement. The enhanced Marketplace subsidies could act as a bridge between Medicaid and the ACA Marketplaces when the PHE ends and many people disenrolled from Medicaid could find low-cost coverage on the ACA Marketplaces, including, in some cases coverage with a zero (or near-zero) monthly premium requirement. However, because the enhanced subsidies are not permanent, future Marketplace enrollees may see steep premium increases when the subsidies eventually expire.

Preventing coverage losses and closing remaining gaps in coverage would help to address longstanding disparities in health, which have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Research shows that having health insurance makes a key difference in whether, when, and where people get medical care and ultimately how healthy they are. Uninsured people are far more likely than those with insurance to postpone health care or forgo it altogether. Being uninsured can also have financial consequences, with many unable to pay their medical bills, resulting in medical debt. As such, future trends in coverage will have a significant impact on disparities in health access and use as well as health outcomes over the long-term. However, beyond coverage, it also will be important to address inequities across the broad range of other social and economic factors that drive health and to address other inequities within the health care system that lead to poorer quality of care and health outcomes for people of color as part of efforts to advance health equity.

More Stories

Empowering Independence: Enhancing Lives through Trusted Live-In Care Services

Major Mass., NH health insurance provider hit by cyber attack

Opinion | Health insurance makes many kinds of hospital care more expensive